A majolica albarello, in 15-16th century style.

This project was a surprise present for my friend Anne, who is seriously into mustard: a renaissance Mostarda albarello, filled with a 16th century Mostarda.

Research & Design

Albarello is the Italian term for these storage jars, which were in general use – not just for medicine. Tin-glazed earthenware (Houkjaer 2005) states that majolica in this form are often apothecary jars and that the shape had its origins in the Middle East (museums often catalogue them as apothecary or drug jars).

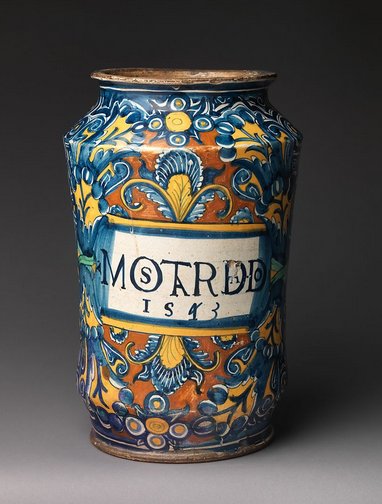

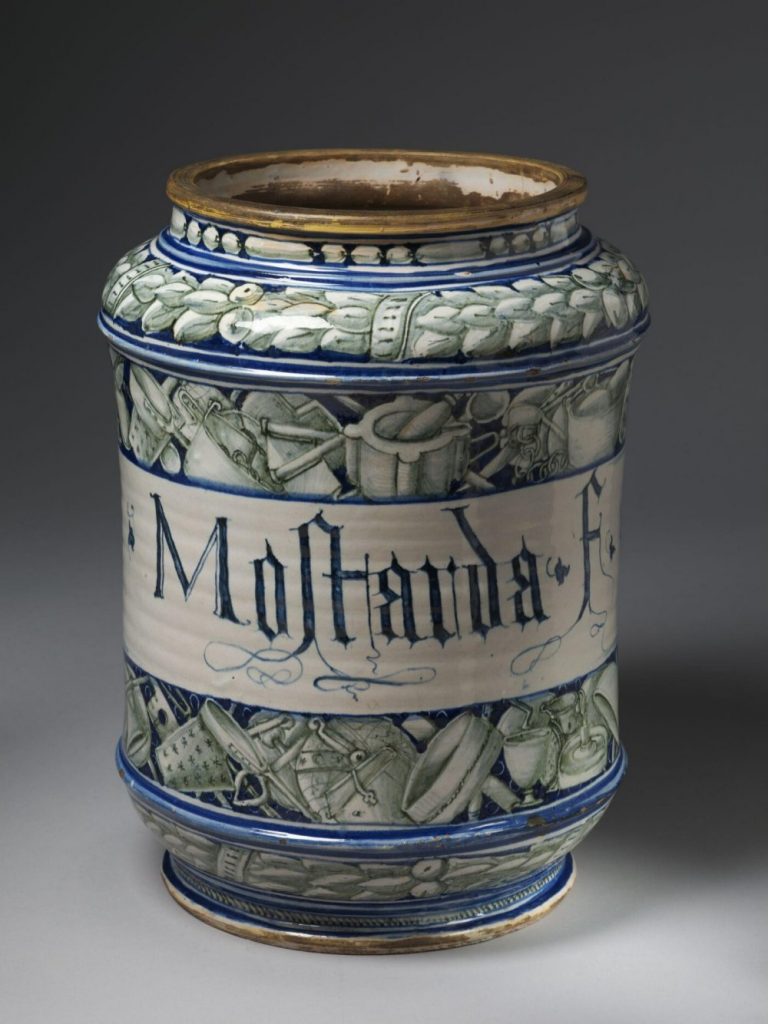

The archetypical albarello appears in the mid 15th century, and continues through the 16th century, with most production in Italy, Spain and France. Some jars show labels and/or images relating to their contents, while others are decorated in foliate, geometric or pictorial forms.

Source: The Met

Source: V&A

Source: V&A

The examples above show 16th century albarello specifically labelled for Mostada, but none of the decorations relate to the contents!

I wanted to refer to the mustard contents and take the aesthetic back to the 15th century, using a more open design. Heraldic emblems are common on these jars, and seemed appropriate here.

My design included the distinctive 4 petalled mustard flower, together with Anne’s heraldic device on the back, based on yet another albarello. The ‘Mostardo’ label is copied from the example from the V&A shown above.

I planned to fill the jar with a suitable mustard and was thrilled to find a suitable recipe in Bartolemeo Scappi’s Opera – my favourite renaissance cookbook (Scully 2008).

Construction

I had done a previous project painting small apothecary jars, so I already had a suitable slip-coated jar to hand, and all the glazes.

I wrapped paper round the pot to make a pattern, then sketched out the key elements of the design – the label and heraldic device. I pricked the pattern with a blunt needle, then used charcoal powder to pounce through the design onto the underglaze.

I used a small flat brush to calligraph the label, then painted the label edges, the device, wreath and the top and bottom borders. Finally, I painted in the mustard flowers to fill the spaces.

Once dry, I sprayed it with hairspray to hold the powdery glazes, then sent it off to be fired.

Meanwhile, I redacted Scappi’s recipe Per far mostarda amabile

To prepare a sweet mustard

(Scappi VI, 199 and II, 276)

Get a pound of grape juice, another pound of quince cooked in sugared wine, four ounces of apples cooked in sugared wine, three ounces of candied orange peel, two ounces of candied lime peel and half an ounce of candied nutmegs; in a mortar grind up all of the confections along with the quince and apples, When that is done, strain it together with the grape juice, adding in three ounces of clean mustard seed, more or less, depending on how strong you want it to be. When it is strained, add in a little salt, finely ground sugar, half an ounce of ground cinnamon and a quarter ounce of ground cloves. It is optional just how mild or strong you make it. If you do not want to grind up the confections, beat them small. If you do not have any grape juice you can do without, getting more quince and apples cooked as above.

The hardest part was getting the candied nutmegs. But it turns out these are popular in Malaysia and a friend in Queensland was able to find some for me and post them!

I was very happy with the result and it made a lovely surprise. I enjoyed the leftover mostarda too – an excellent, sweet and spicy condiment, excellent with cold meats, and clearly the origins of the modern Italian Mostarda.

Afterthoughts

In a lovely case of art imitating art, my gift of a Mostarda jar was immortalised on this beautiful piece, made for Anne in 16th century style by the wonderful scribe Master Giles Leabrook.