A pair of cloth-cut hose, suitable for a 16th century woman in western Europe, or for 16th century men as netherstockings.

I made my first pair of hose in 2006, to replace the modern long socks I’d been wearing with something more historically correct for my early 16th century German wardrobe, both middle class and noble.

Hose were worn by both women and men throughout the medieval and early modern periods across western Europe in various forms. The medieval forms had an instep seam to shape the foot and were basically symmetric, with right and left feet made to the same pattern.

In the 16th century, the cut of the foot changed significantly, with side gussets replacing the instep seam and in some cases, distinct right and left feet. This new style was worn across western Europe for both cloth-cut hose and knitted ones – and can still be seen on modern knitted socks.

In addition to being worn by women, these 16th century short hose were also worn by men as netherstockings, sometimes sewn to the base of their canions.

Research & Design

Textiler Hausrat (Zander-Seidel, 1990) notes that Albrecht Dürer refers to Knee-hose his wife bought in Antwerp in 1520, and images from the time show knee-high hose fastened with a garter, but that there is very little information available on women’s hose in 16th century Germany.

Examples of women’s hose in art are rare, as they hidden by the long skirts. By the 16th century, manuscript marginalia (always a fruitful source of images) are no longer common, but there is the occasional depiction of a women getting dressed or undressed.

Source: Wikimedia

(Note that the image by Israhel van Meckenem is NOT evidence for women wearing underpants. The title Verkehrte Welt means ‘The world turned upside down’ – in this case, the text makes it clear the pants represent gender-role reversal).

We know from written accounts that women were still wearing cloth-cut hose to the middle of the 16th century and beyond – even at the upper classes. In Italy, cloth-cut hose in wool were still still appearing in woman’s trousseaux as late as 1574 (Landini and Niccoli, 2005).

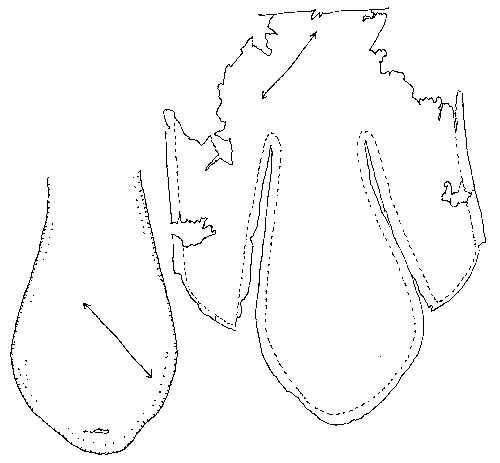

Unlike earlier hose, the 16th century cut does not have an instep seam. Instead, the fabric extends from the leg down to the toe to provide a smooth instep. Shaping is achieved with with a separate sole and triangular gussets under the ankles, either separate or attached to the sole, with variations in the sole shape.

This example from the London finds (Crowfoot et al, 1992), has a split heel and Italian examples often have a pointed heel. The Mary Rose finds (Gardinier (ed), 2005) include hose fragments with a broader heel shape, which is very similar to the pattern I use.

Source: Landini RO & Niccoli B (2005)

Source: Gardinier J (ed) (2005)

Illustration: Robyn Spencer

Hose were usually made of wool, although linen is also mentioned frequently, sometimes worn under woollen hose, as with the Spanish linen understockings shown above.

Queen Elizabeth’s Wardrobe Unlock’d (Arnold, 1988) notes that the Queen wore cloth-cut hose in linen, wool (cloth and flannel) and silk (sarsenet) until 1577, when supplanted by knitted items. These hose were cut on the bias, with a seam at the back, stitched with silk.

The Museum of London finds include an example of 16th century hose made of a 2:2 worsted twill (Crowfoot et al, 1992), while finds from the Mary Rose include remnant hose cut from plain woven, napped woollen cloth (Gardinier (ed), 2005). These hose would have been sewn with linen thread, which has not survived, but the holes show the construction.

I have made cloth-cut hose in many fabrics – heavy linen, tabby-woven cloth, twill and worsted – to suit the weather and class of the outfit. Textiler Hausrat (Zander-Seidel, 1990) lists hose in wills in several colours – white, yellow, red, black and green.

Garters

Garters were essential to hold up women’s short hose. These could be made of a narrow band of textile, tied under the knee, as seen in the Lotto painting below. This might be a strip of fabric, tablet woven or even sprang, as in the late 16thc silk example below.

I have seen also seen a plain woollen knitted garter in the Museum of London storage collection (not published online). It was worked in garter stitch, 9 stitches wide (2cm), with a broader central section and narrower ties – similar in shape to this later example in knitted silk.

Source: MFA Boston

Source: MFA Boston

It is possible that women also wore buckled garters – I have not seen any buckles on depictions of women’s garters but some images, such as the van Meckenem woodcut above, show a band with no obvious tie.

Patterning

This style of hose is trickier to pattern than the earlier styles, but do give an excellent fit. You can pattern them based on measurements of the foot and leg, using plain woven fabric on the bias. This approach gives you a custom fit – regardless of your shape and size.

The patterning process is not difficult, but some steps needs detailed explanations. I have created a set of step-by-step instructions for patterning your custom hose, available as a free PDF download:

How to Pattern 16th Century Short Hose

Construction

A 2:2 twill wool is ideal for these hose as it provides maximum stretch, and was common in the 16th century for hose. You can also make them from tabby woven wool, worsted wool or solidly-woven linen. It’s important to wash your fabric as you plan to wash your hose. If you get any shrinkage, wash a couple of times.

Once the test run is working well (see patterning link above), I lay out the pattern on the fabric on the true bias. Cutting on the bias is inefficient, but cutting several pairs of hose at once does reduce the waste. The sole sections can be fitted in around the main pieces. Keep some scraps for patching!

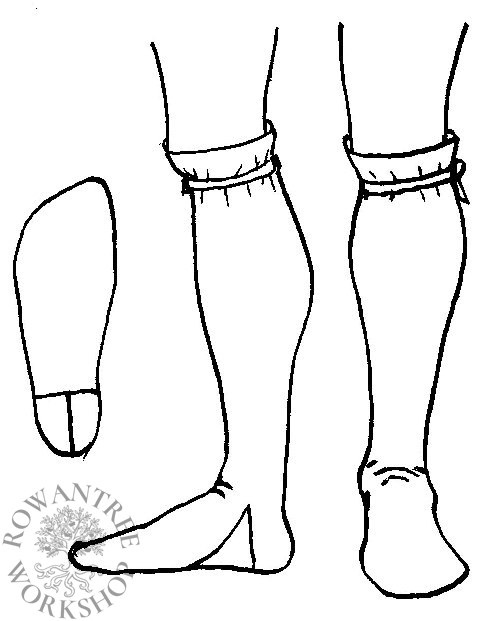

Unlike making earlier styles, we start with the back seam. Because each fabric has a different amount of give, pin along the back seam and carefully try the hose on. It should fit snugly under your heel and smoothly around your leg – adjust pins as needed. Check you can still get it over your foot (adjust if needed), then mark the new seam line. Transfer markings to for the other leg (mirror image).

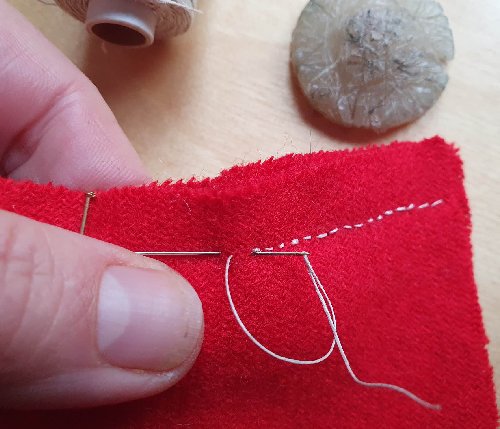

This back seam needs both strength and give. I have sewn this in backstich using (waxed) linen thread, in line with the historical examples. You can also sew this seam by machine using a long narrow zig-zag to provide stretch (I use 1.8 width and 3.5 length). Trim seam allowance to 1cm, a bit smaller over the heel.

To keep the seam from bunching, open it and sew a row of small running stitches 2-3mm from the seam on each side, pausing every 5cm or so to stretch the stitches and add a lock-stitch. This ensures the seam still has some ‘give’ when in use. Alternately, you could fell the raw edges down with whipstitch.

Now on to the sole. If you have very well-fulled wool, you could sew this as an overlapped seam, whipping both sides, as for medieval hose (and the Mary Rose example, in tabby woven wool). I find that twill frays too much, so here I have used a run-and-fell seam to attach the sole. I also use this approach for linen.

First, pin the sole section at the toe, then match the middle of the sole to the back seam, with an uneven seam allowance – the sole piece is set 5mm longer. Pin this seam at each end – the corners of the sole will match the end of the cut, with some overlap at the point. Sew a 7mm seam using running stitch.

Pin the rest of the foot and sew it in the same way, with an uneven seam allowance. Then fold the seam allowance over, away from the sole and whip down the raw edge – easier to do using a darning mushroom.

Finally, I fold a double hem and slip-stitch this down (for fulled wool, a single hem would be enough).

Despite the seam under the heel, these are really comfortable to wear! I have made (and worn out) dozens of pairs in woollen wool, worsted wool and heavy linen.

Afterthoughts

I am hard on my socks, and equally so on my hose, so I darn and patch them to keep them in use – much less work than making a new pair. I use a fine wool thread (Madeira) for darning small holes, working over a wooden darning egg or mushroom.

Crowfoot et al (1992) noted that the London finds included several elliptical bias-cut pieces with stitch marks around the edge, which were probably patches for the toes and heels of hose.

My patches end up similar shapes – I cut them by eye to match the hole and a margin, then whip them on with the same fine wool thread I use for darning. Then I whip around the hole, making an overlap seam. The patches felt in well after the first use, and don’t feel lumpy.